By Teresa Hartford

<span style="color: #999999;">British Columbia native, big mountain pro skier and award-winning star of Teton Gravity Research (TGR) films, Nick McNutt pushes the laws of physics with his aerobatic, smooth like butter, switch landings that have earned him accolades from the elite ski community and pioneers of the sport.

What does it take to have Nick’s mental toughness to ski heights that are death-defying in some of the world’s most remote corners? SGB found out when we sat down with Nick before the premiere last month of TGR films “Winterland,” in which he stars.

You grew up loving to ski. Did it take over other sports? Skiing was always the one. Both my parents were skiers, and they got me and my sister hooked when we were very young by taking us up on the hill to ski every weekend. After high school, moving to Whistler was a natural evolution.

Did you dream of being a pro skier? I always thought it would be cool, and today I am. Life is pretty darn perfect.

Do you have a formal fitness program you follow in the off-season? I don’t have a strict plan.

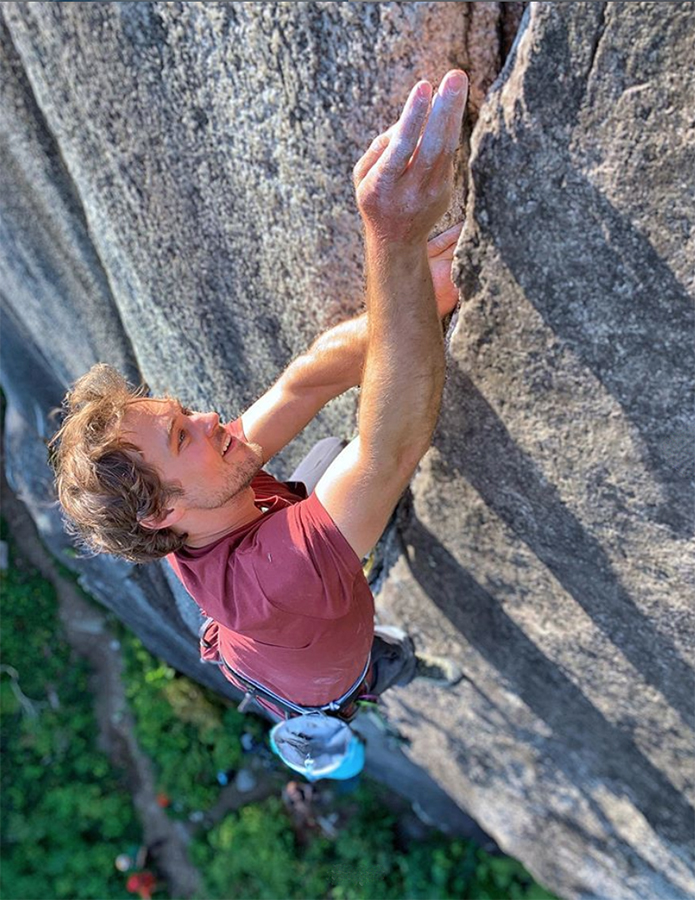

The big thing in the offseason is staying in shape. I’m passionate about rock climbing, mountain biking, trail running, and mountaineering—outdoor activities that involve cardio and leg strength. Rock climbing is good for your headspace and makes your fingers strong. Mountain biking and trail running are great for leg strength and cardio.

The big thing in the offseason is staying in shape. I’m passionate about rock climbing, mountain biking, trail running, and mountaineering—outdoor activities that involve cardio and leg strength. Rock climbing is good for your headspace and makes your fingers strong. Mountain biking and trail running are great for leg strength and cardio.

I would rather work out in the mountains than in the gym, but if I am indoors, I work on balancing exercises with a Bosu ball and squats with a medicine ball. I choose dynamic exercises that fire up the micro-muscles, because I need to be at a high level of strength in those areas to sustain the crashes that I take and for as hard as I push. And as you get older, injury prevention is key.

Have you trained this way in the off season since early on in your career? After my first injury, it was at the recommendation of a physiotherapist to focus on the small fire muscles. Skiers generally have strong quad muscles, but that’s almost counterproductive for energy prevention because it creates an unevenness on your ligaments and knees.

I don’t focus on the main quad muscles but rather hamstrings, calves and core, which includes the lower back (rock climbing is good for the core). I’ve had a back injury and a disc injury, so I do back extensions with weights and include stretching. Having a strong core is key for injury prevention, especially during the crashes that I take where I’m tumbling down the mountain.

The only protection your body has when you’re skiing those extreme heights and “tricking” is the helmet on your head. Is that ever front-of-mind? It can mess with your head, but I don’t think anyone of us got to the level of skiing that we’re at without crashing.

I’ve been crashing more or less all my life, and it’s one of the most important skills to have as a freeskier to be able to crash well and to know when it’s time to give in to the crash. As soon as you start to fight what’s happening—going down in a certain direction—it’s hard to stop, and if you try, that’s when you get hurt the worst. Sometimes its more about staying relaxed, committing to the tumble, not stopping the inertia, and being ok with that.

I’m accepting of the reality of what I do, especially with the freestyle tricks where I’ll crash multiple times before I nail what I’m trying to do. It’s part of the game and is normal.

How do you stay motivated when you’re not mentally engaged, or you’re injured? The motivation is always there, and if for some reason I’m exhausted, it’s a sign to take a rest day, and then the motivation comes back. My routine is free-flowing and self-structured. If it feels like the wrong day to go skiing, I’ll listen to that. In general, that keeps me motivated to keep going for the right reasons, and I have fun doing it.

Are there technical moves that you’re body struggles to execute? How do you manage the frustration? As a freestyle skier doing aerial maneuvers, I get frustrated with muscle memory. If you engrain the tricks that I do at a young age, you don’t have to think too hard about setting your body into the air. But there are specific orbital axis’ that can be difficult to get if your muscle memory isn’t there. I pick my battles, and I know what comes naturally. I work with the muscle memory strengths I have rather than forcing the ones I don’t.

I don’t need to do a particular trick, but I’m always willing to learn; however, it’s easier when your young because you can spend your adolescence engraining it to muscle memory—which I’ve done with several tricks. There are some tricks, for sure, that have been elusive and where the air awareness and muscle memory doesn’t click on a certain axis, which can be annoying at times, but, like most skiers, I have ones that I’m comfortable with and ones that feel less comfortable doing. It’s normal, I think.

Does “trick” skiing alter your perception of moving through the air differently than if you are skiing on a straight trajectory? Sometimes I find it’s more challenging to hit a stylized jump in a straight line and land. If you’re comfortable with different rotations, they allow you to take away the hyper-focus of making sure you are very still, and that you are going in a straight line. When you’re focused on the rotation, you’re not focused on the A to B but rather the rotation. It’s only at the tail end that you switch your focus to the straight line. You haven’t spent your flight time focused on it.

It goes back to muscle memory. When you have it figured out, it’s second nature. For example, doing a 360 off a jump, sometimes I find that’s easier than doing a straight line in the air.

What are your favorite listening and safety devices? I use my iPhone for music and Garmin inReach Mini when I’m skiing somewhere I’ll be out of service. It’s also great for navigation. I don’t feel under-equipped with my InReach Mini.

Photos courtesy Nick McNutt, TGR, The North Face, Atomic