From Montgomery, AL, to the Midwest and the Rocky Mountains, artificial whitewater parks are sweeping across the U.S. as communities embrace the economic potential of their local waterways and recognize the recreational and revenue value.

In Colorado alone, one of the states leading the trend, new whitewater parks have opened in the Colorado towns of Eagle, Canon City and Ft. Collins, joining existing parks in Salida, Buena Vista, Montrose, Steamboat Springs, Lyons, Golden, Pueblo, and Glenwood Springs. In addition, new parks on the horizon include Craig, Rifle and Palisade and Denver’s RiverMile multi-use development slated to turn its South Platte riverfront into a water park for floating, fishing and recreation.

“Two trends have overlapped, creating a huge interest in them,” said Scott Shipley, founder of whitewater park design firm S20 Design and Engineering. “First, there’s a general trend of Millennials pulling the rest of us outdoors on adventure vacations with more people pursuing outdoor adventure. Then the pandemic hit and, suddenly, the only game in town is an outdoor adventure. People love having an adventure to pursue right at home. Whitewater parks bring that adventure into your backyard. Millennials aren’t happy sitting by the pool. They want a vacation that doubles as an adventure, which whitewater parks deliver, and the parks bring money into their communities.”

The Rocky Mountains aren’t the only area to cash in on the craze. The Midwest and West Coast also see river parks under development. River park design firm Recreation Engineering & Planning is breaking ground on June 22 on a new river park in Franklin, NH. It is also designing new parks on the Russian River in Healdsburg, CA and on the Wenatchee River in Leavenworth, WA. In addition, the firm recently completed courses in Andover, MI; Dayton, Ohio; Stoughton, WI; and Charles City, IA.

“Instream river recreation and interest in whitewater parks are exploding,” said REP founder Gary Lacy. “And the economic impact the courses have on their communities is more than anyone predicted.”

Indeed, local communities and visitors use the parks for everything from kayaking and rafting to SUPing, river surfing and floating on inner tubes. But, more importantly, the communities also use the parks to swim and picnic, revitalizing downtown corridors in the process.

“The commonality is that people love being on or next to the water—whether it’s surfing, having lunch or dangling their toes in the water,” Lacy said. “And to see the transformation in towns that embrace these parks is amazing. They become vibrant focal points of their communities.”

The trend is not new; it has only accelerated. The world got its first look at the concept when whitewater slalom appeared in the 1972 Olympics on a fast-paced, artificial course in Augsburg, Germany. Wausau, WI and South Bend, IN built slalom courses in the early ‘80s, and Denver got into the game early with Confluence Park on the South Platte constructed in 1974 to modify a dangerously low-head dam.

With $80 million in federal matching funds, Denver’s River Mile multi-use development lies upstream of the original park on the South Platte with its river restoration by S20 Design its fundamental purpose. “It will be one of the most significant river restorations undertaken by a private enterprise, anywhere,” said Greg Murphy, president of project manager Calibre Engineering.

When Golden, CO built its Clear Creek Whitewater Park in 1996, the U.S. saw a publicly funded course built for whitewater for the first time. “Golden broke the mold by allocating municipal funds solely for a destination whitewater park,” said Lacy. “They approached it just as they would have a new softball field. The concept took off from there.”

The recreational benefits of the parks are apparent. First and foremost, like climbing gyms for climbers and terrain parks for snowboarders, they have made the sport more accessible, offering paddlers and other users the opportunity to get a quick floating fix eliminating a drive to the mountains.

Located on the Winnipasake River, the river park, breaking ground in Franklin, NH, “is going to revitalize a deteriorated section of historic downtown that has long been neglected,” said REP’s Mike Harvey, adding that the town has a ski area that’s been turned into a mountain biking resort. The addition of a whitewater park will add more outdoor vitality to the region.

These parks are also creating a boom for local economies. Golden’s course was built for $165,000. Studies performed in the early years estimated it contributed more than $1.4 million annually to its economy. “It’s a very big draw for the town,” said the City’s Communications Manager, Sabrina D’Agosta, at that time. “People are becoming aware of Golden as a destination because of it.”

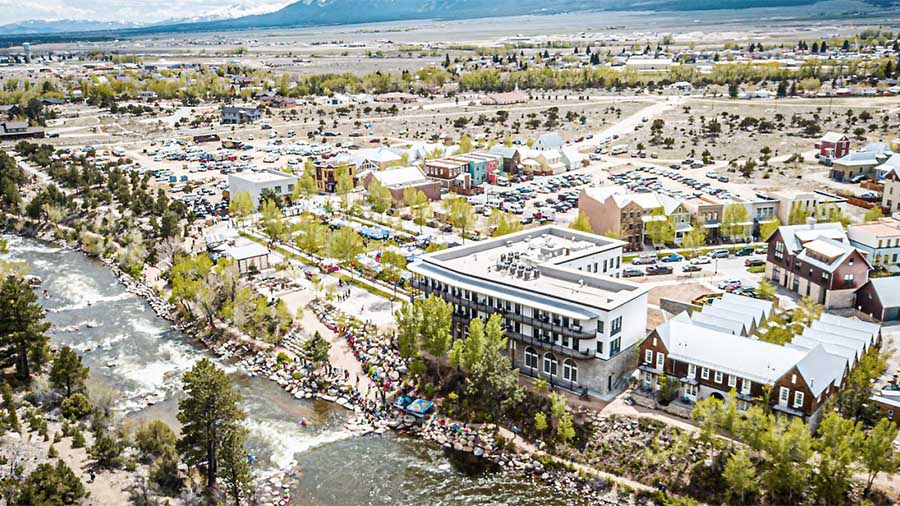

A park in Salida, CO, built for $300,000, has also been successful. “The energy coming from the river corridor impacts all of downtown,” maintains the Arkansas River Trust’s, Mike Harvey. “On a nice summer day, it’s like South Beach, Rocky Mountain-style. Moms drink lattes on the bank while their kids play in the eddies, and paddlers from world champs to beginners surf the park’s waves.”

Whitewater parks are also being created to convert dangerous and outdated low-head dams into recreational amenities, as is the case on the Kansas River in Topeka, KS, and a new course in Waco, TX, created a surf wave from a dam bypass. “There are a ton of low-head dams across the country that don’t serve a purpose anymore and are outdated and dangerous,” said Lacy’s son, Spencer, who also works for REP. “It’s a great way for communities to get rid of them and turn them into focal points of their towns.”

The parks are also proving their worth in establishing flows. In 2001, Golden won a decision from the Colorado Supreme Court guaranteeing minimum flows for its park, creating a new fork in the state’s water-rights landscape. The result was precedent-setting, with its newly coined Recreational In-channel Diversion (RICD) water right establishing for the first time that recreation can be as beneficial a use of water as agriculture, industry and development.

“That decision was the big breakthrough for recreational water rights cases,” said water attorney Steve Bushong of Denver’s Porzak, Browning and Bushong, which has since represented, and won, similar settlements for parks in Vail, Steamboat Springs, Gunnison, and Chaffee County. “These municipalities are just trying to protect their investment, and it’s the water parks that provide the diversion and control necessary to meet the right’s requirements. It’s the new West, showing that recreation has come of age.”

Often, several entities come together for a water park project. A course in Pueblo, CO, was built as a fish passage by the Army Corps of Engineers, with recreation a coincidental byproduct. Buena Vista’s South Main Project Upstream is a partnership between the town, a local land developer and GoCo Lottery grant. A kayak course on the North Platte in Casper, WY, was funded by British Petroleum as an environmental remediation package, and in Reno, NV, a partnership between local casinos and the city.

Partnerships like these have also come together on a much broader scale for larger, recirculating projects that include adjustable wave features, George Jetson-like conveyor belts that carry paddlers back to the top, large pumps to recirculate water, and a daily fee for users.

In chronological order of construction, these courses include the $23 million Adventure Sport Center in McHenry, MD; $37 million National Whitewater Center in Charlottesville, NC; and RiverSports Rapids Center in Oklahoma City, OK completed in 2015. These courses will soon be joined by the country’s fourth recirculating course, the $50 million Montgomery Whitewater Park in Montgomery, AL, which broke ground June 10, will open in 2023. Designed by S20 Design, the 120-acre recreation and entertainment complex will offer commercial rafting, a recreational passage, serve as a venue for elite World Cup competitions, and offer rock climbing, zip lines, bike trails, shipping, beer gardens and more.

“It’s the type of forward-thinking, quality-of-life project that will grow our population base, attract new visitors and create additional revenues,” said Montgomery County Commission Chairman Elton Dean. “We look forward to it being the destination hotspot and a deciding factor for new residents to call Montgomery home.”