After spending a few days reviewing the data in the most recent study from the International Council of Shopping Centers (ICSC) assessment of the effect of opening and closing retail brick & mortar stores on online sales for the retailer opening or closing those doors, or what ICSC has dubbed the Halo Effect, SGB Media took a look at the data surrounding the generational aspects of the survey conducted by ICSC and strategy and research firm Alexander Babbage and the resulting study report.

ICSC said their latest research digs into hundreds of market areas to provide a hyperlocal analysis of how a new store could drive online awareness, reinforcing the brand’s sales cycle. While new stores continue to billboard brand awareness, they also directly correlate to increased online and in-store sales.

According to ICSC’s research, in-store is the preferred channel for all generations. However, SGB Media found it interesting that the generation of shoppers that ICSC found most likely to want to see, touch, and try products in a physical retail store isn’t the one that’s settling into their 30s and 40s, focusing on advancing careers or shouldering mounting caregiving responsibilities. Based on the data, it isn’t the generation that’s eyeing retirement or the one that’s already left the workforce with money and leisure time to spare. Surprisingly, the generation most researchers contend are most likely to shop online and buy based on social media influencers, the so-called digital natives that comprise Gen Z (ages 11–26 in 2023) are the ones that ICSC found prefer shopping in-store the most among almost all generations.

Gen Z was more likely than Millennials (ages 27–42 in 2023) and Gen X consumers (ages 43–58 in 2023), and comparable to Boomers (ages 59–77 in 2023) to shop and buy in-store. The discussions in many a product or brand strategy meeting invariably contend that Gen Z aren’t tactile shoppers. They don’t have the same type of relationships earlier generations before them had growing up without the digital tools that have been commonplace in their lives since birth.

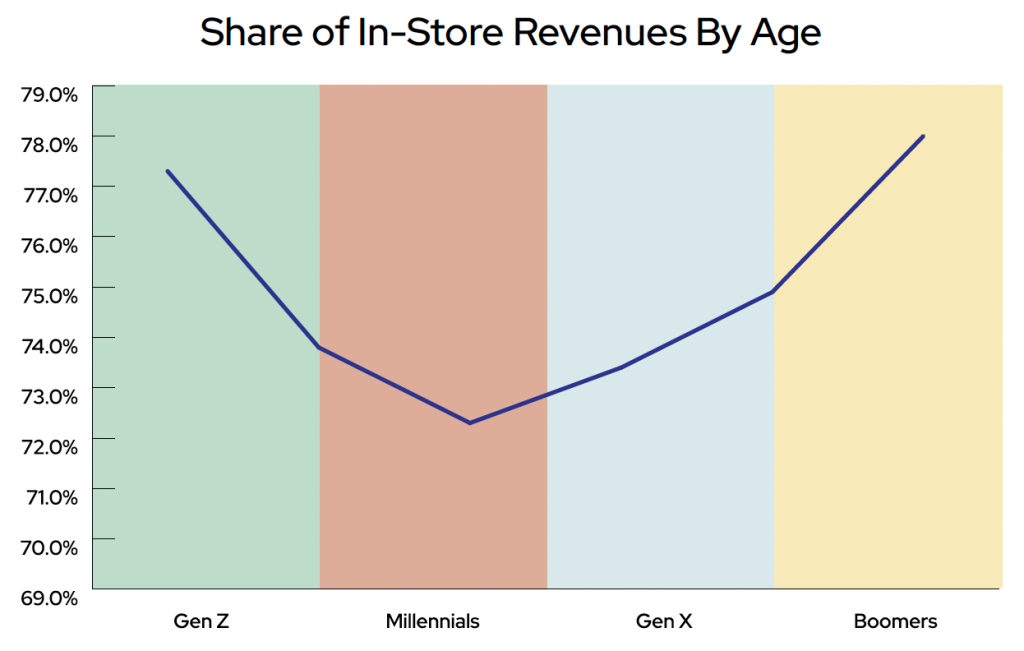

In ICSC’s 2023 Gen Z report, the researchers said they found that nearly all respondents (97 percent) shop at brick & mortar stores, thanks to the immediacy with which they can walk away with a product. The trade association’s recent analysis exploring the Halo Effect shows that Gen Z consumers are shopping in-store more than Millennials and at a similar rate to Boomers. Overall, the trend follows a U-shaped curve as seen below. Gen Z is nearly equal to Boomers in the share of revenues they drive in-store, compared to online. On the other hand, Millennials are last among all generations, followed by Gen X. The U-shaped curve generally holds true across store categories, such as apparel and discount department stores.

ICSC wrote that while Gen Z grew up entirely with digital and mobile technology at their fingertips, their penchant for in-store shopping at times even exceeds that of the generations that grew up shopping in physical stores. ICSC concluded they see the convenience, ability to try new products, and relationship-building aspect of in-store shopping as value-added and “back up that perspective by opening their wallets.”

“Gen Z are digital natives, but it’s clear that they’re also retail revivalists, helping to play a major role in revitalizing the physical retail landscape,” the report states.

ICSC also noted a few Gen Z voices that reflect some of this assessment.

Erika, 19, Tennessee

“I’m 5′2″, so a lot of clothes that are mass produced don’t fit me. That’s why I prefer going in person to shop and build trust with a brand. I’m not very adventurous when it comes to shopping online because I’ll have to spend a bunch of money then send it back because whatever I just bought won’t fit my torso or my legs. And I know people at the stores that I frequent. There are workers that know me by name. It’s a consumer relationship that you can’t get from behind a screen. If I need a lip gloss that’s running out, that won’t stop me from ordering online. But there is the instant gratification of going in-store and being able to pick out and see what I’m buying.“

Henry, 21, California

“I don’t do a particularly large amount of shopping. The brands I consistently buy from don’t have a physical store. Most of it is word of mouth or they’re involved in a space I like, such as a ski brand. Maybe there’s one special specialty shop that carries them or they have them at their manufacturer, but it’s mostly online. For buying skis or a winter jacket, I usually try to do that in-store. I like having the physical item there. It’s easy to see how it measures and get the feel of it. I like having all the options in front of me, rather than having to visit five different manufacturers’ websites.”

Anna, 19, Georgia

“I definitely prefer in-store shopping as a social event with my friends. I like in-store shopping for trying things on or seeing something online that I was really excited about. What’s cool about in-store shopping is you get to just be there physically and see different colors and styles. But if I really need something or know exactly what I want, I tend to order that online. Still, I think experiences for me are definitely more important than my clothes. My parents have taught me the value of experiences over just buying things all the time.“

Conclusion: Expanding the Halo

ICSC concluded that physical stores are one of the catalysts for consumer trust.

“A positive store experience can help a brand build or strengthen a connection with its customers—one that may help them extend the relationship beyond in-store transactions,” ICSC wrote in the report. “This analysis of the financial impact of the halo effect offers convincing evidence for established and emerging retailers to maintain a strong network of physical stores.”

The calculus for closing stores, according to BMO Capital Markets Senior Retail Analyst Simeon Siegel, often comes down to the view that retailers are holding excess space when there might be other economic factors, such as pricing and positioning, at play.

“Ultimately, it’s a decision that offers an opening for competitors to step into the void,” he wrote. “Closing a store often feels like a clear-cut action,” Siegel suggested. “The problem with North American retail is not an over-saturation of stores, but an over-saturation of discounts. People have watched the brand value they create fade. It’s not to say that you shouldn’t prune stores if they are cashflow negative, but not when the recapture rate of sales on a closed store is materially lower than it was initially hoped to be.”

Methodology

An analysis by the strategy and research firm Alexander Babbage for ICSC examined $848.1 billion of in-store and online spending by zip code to quantify the impact of opening and closing stores. The analysis covered in-store and online sales of 69 retailers, including 2,103 stores in 50 states plus Washington, D.C., from 2019 to 2022. The data was computed by reviewing the 13 weeks following the opening or closing of a store. The study excluded the two weeks before and after the week of the store closing or opening to minimize any final sales for closing or honeymoon periods following the opening of a store. The study included established retailers across six categories: apparel, big box specialty, cosmetics, department stores, discount department stores, and home stores. The study also included emerging retailers identified from a list of 140-plus direct-to-consumer brands across multiple categories. The ICSC analysis of the apparel category highlighted a difference based on momentum. Where applicable, the study highlighted two apparel sub-groups—brands that were mostly expanding their total number of stores and brands that were mostly shrinking their total number of stores.

For more information on ICSC’s latest report, go here.

Photo courtesy AdobeStock, graph and data courtesy ICSC